Welcome and thank you to Dale, Marilyn, Miacello, and Elaine Fine. I see from Elaine's profile she writes CD reviews and program notes, composes, and plays viola and violin. Oooo. Miacello is another of us blogging cellists; there's getting to be quite a family of us. Dale's got some funny stuff on his blog. And Marilyn? No blog or profile yet, a woman of mystery.

PS; And also welcome to Coaster Punchman. Yes, I'm with you, tell those kids: indoor voices!

This weekend, barring complications, my wife and I will go to a weekend New Years Camp put on by The California Traditional Music Society. At this point some there's some doubt my wife will go, she's ill (getting the cold I had last weekend) and she's got a lot of work to have done this week. Her job entails a lot of writing. I do hope she goes. I'll do what I can to help her make it out there.

Old World or New, Sacred or Profane

Wednesday, December 27, 2006

Friday, December 22, 2006

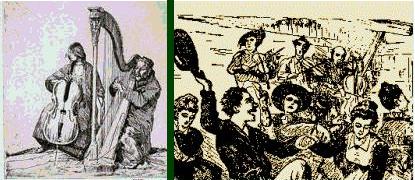

David Allan's The Highland Wedding

Rather than write, I'm posting a painting: The Highland Wedding at Blair Atholl (1780) by David Allan (1744-1796). The fiddler represented is the famed Niel Gow (1727-1807), the cellist is his brother Donald. According to the Dunkeld Cathedral website, Donald's sensitive accompaniment inspired Niel to play his best.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Email Duet

PFS and I have collaborated on a duet on Red Is The Rose via email.

Well, by the end it's more like a quartet. PFS recorded first and plays melody throughout 4 times. On the first time I play pizz bass/strum. On the second time I play an arco lower harmony part, usually a sixth or third below the melody. On the third time, through the magic of multi-track recording, I play both the pizz and the arco at the same time. For the 4th time I add to that another arco part, this one above the melody with mostly long tones.

While some notes are not precisely what we'd like, I think there are some spots that came out quite nicely. I hope we do more soon.

Red Is The Rose

Well, by the end it's more like a quartet. PFS recorded first and plays melody throughout 4 times. On the first time I play pizz bass/strum. On the second time I play an arco lower harmony part, usually a sixth or third below the melody. On the third time, through the magic of multi-track recording, I play both the pizz and the arco at the same time. For the 4th time I add to that another arco part, this one above the melody with mostly long tones.

While some notes are not precisely what we'd like, I think there are some spots that came out quite nicely. I hope we do more soon.

Red Is The Rose

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Common-Practice Era music "theory"

Who out there has some so-called music "theory" study or training? By that, I mean (a) how to form the different types of chords, (b) inversions, (c) how to read figured bass, (d) doubling rules in 4-part harmony, (e) types of motion, (f) voice leading, (g) what chords most easily follow what other chords, (h) the types of non-harmonic tones and how they are used, (i) ways to modulate..., y'know, fun stuff like that.

My high school band teacher brought someone in to teach us that stuff for a few sessions each year. I loved it and so it really struck a chord, so to speak, with me. I could often be caught studying the conductor's scores whenever I had the chance. I learned to read all the different transpositions. What really intrigued me were scores or parts of scores that ignored the "rules". How did they know it would work? It seemed like magic. Of course, now that I'm much older and presumably wiser I know for sure that it really is magic.

I get the feeling most adult beginners and even most child beginners don't get enough instruction in that stuff. Isn't there more to playing an instrument than putting finger X on spot Y to get note Z, just because that's what's on the paper?

Or maybe it's just me and it's not that important for most instrumentalist folks.

Reposted from CBN, below are links to written music and midis for God Rest Ye Merry Gentleman with two different accompaniments. While both accompaniments are for the same tune, the two accompaniments are not at all compatible!

The first accompaniment is the traditional bass line sung by bass voices or played on piano since who-knows-when. It conforms to the collection of rules practiced during the Common-Practice Era, ie, the kind of rules one learns in "theory" class. No parallel fifths or octaves, no 2nd inversions except under special circumstances, no doubling the 3rd except under special circumstances...

The second accompaniment, mostly in double stops, ignores some of those rules. Mr. K would have given it a big ol' F! Make that F minus! There's nothing like telling a kid he can't do something to make him do it (35 years later, even!).

I've prepared two midis, one with the traditional bass accompaniment and one with my own thing.

PDF of all 3 parts

MIDI with CPE-stype bass

MIDI with non-CPE bass

PS: I decided this cryptic post was necessary to set-up for Chapter 4, so that's why it's here.

My high school band teacher brought someone in to teach us that stuff for a few sessions each year. I loved it and so it really struck a chord, so to speak, with me. I could often be caught studying the conductor's scores whenever I had the chance. I learned to read all the different transpositions. What really intrigued me were scores or parts of scores that ignored the "rules". How did they know it would work? It seemed like magic. Of course, now that I'm much older and presumably wiser I know for sure that it really is magic.

I get the feeling most adult beginners and even most child beginners don't get enough instruction in that stuff. Isn't there more to playing an instrument than putting finger X on spot Y to get note Z, just because that's what's on the paper?

Or maybe it's just me and it's not that important for most instrumentalist folks.

Reposted from CBN, below are links to written music and midis for God Rest Ye Merry Gentleman with two different accompaniments. While both accompaniments are for the same tune, the two accompaniments are not at all compatible!

The first accompaniment is the traditional bass line sung by bass voices or played on piano since who-knows-when. It conforms to the collection of rules practiced during the Common-Practice Era, ie, the kind of rules one learns in "theory" class. No parallel fifths or octaves, no 2nd inversions except under special circumstances, no doubling the 3rd except under special circumstances...

The second accompaniment, mostly in double stops, ignores some of those rules. Mr. K would have given it a big ol' F! Make that F minus! There's nothing like telling a kid he can't do something to make him do it (35 years later, even!).

I've prepared two midis, one with the traditional bass accompaniment and one with my own thing.

PDF of all 3 parts

MIDI with CPE-stype bass

MIDI with non-CPE bass

PS: I decided this cryptic post was necessary to set-up for Chapter 4, so that's why it's here.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Busy Time

I've been away from computers and the Internet the past week. Part of it is my wife's mom passed away this weekend. Also issues with my daughter. Twelve years old and the moods are raging!

I also played and sang in a show at church: "A Time for Christmas". You may have heard of it, it's making the rounds. For some parts I played cello in the small orchestra, and for some of it I sang in the choir. Also, there was my stellar acting in a non-speaking role as Shepherd #2. My robe had been fashioned from the remains of an awful, apparently 70's vintage, curtain. Shepherd #1 had refrained from shaving for the last two weeks. He looked just like the late Yassir Arafat. If the costumes weren't so bad we would have looked like a bunch of middle-aged over-the-hill terrorists.

Thank you to Robin for her comments on what's important in teachers. I'm surprised there's not more comments about teachers, here or at CBN. For something that is so important, I'd think folks would give a lot of thought to what they want from teachers.

Also, I know I owe PFS something. Soon!

I also played and sang in a show at church: "A Time for Christmas". You may have heard of it, it's making the rounds. For some parts I played cello in the small orchestra, and for some of it I sang in the choir. Also, there was my stellar acting in a non-speaking role as Shepherd #2. My robe had been fashioned from the remains of an awful, apparently 70's vintage, curtain. Shepherd #1 had refrained from shaving for the last two weeks. He looked just like the late Yassir Arafat. If the costumes weren't so bad we would have looked like a bunch of middle-aged over-the-hill terrorists.

Thank you to Robin for her comments on what's important in teachers. I'm surprised there's not more comments about teachers, here or at CBN. For something that is so important, I'd think folks would give a lot of thought to what they want from teachers.

Also, I know I owe PFS something. Soon!

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

A Road to Cello - Chapter 3

The festival gave me incentive to pursue an instrument. Something other than trombone, my high school/college instrument. It had served me well, but now it was time for something different, but what?

The memory of the washtub bass thumping in the mist persisted. The music of that weekend was dominated by high range instruments. String bass and washtub bass, along with just some guitarists who emphasize bass notes, were the principal exceptions.

I did a little on-line reseach into washtub bass and found that, while there are no instruction guides at all on how to play one, there are many variations and plans on how to make one. One design in particular appealed to me, dubbed Tub-o-Tone by it's inventer, Lauren Miller. It has a fixed neck, a single tunable string, and a simple, to-the-point, no-frills, sound efficient design that appealed to me.

In my research I learned that washtub basses and harps share something unique in the string instrument world. Other instruments, i.e. those with bridges perpendicular to the string, transmit vibrations to the sound chamber at the same pitch as the string itself vibrates. One cycle to one cycle.

Harps and washtub basses, on the other hand, don't have bridges. The string attaches directly out of the sound box. In those cases the top of the sound box is pulled up and let down twice for every one cycle of the string. The pitch one hears from the sound chamber is twice the actual pitch of the string. Oooo, Cool! So that explains how those guys can play notes in the string bass range with ordinary clotheslines at low tension! It also explains how those long thick nylon harp strings sound higher than it appears they should.

By the end of the summer of 2002 I was in the Home Depot selecting materials and building my very own Tub-o-Tone. By fall I was attending local jams. Suffice it to say my unique home-made instrument got a lot attention and compliments; my playing, well, not nearly so much.

But it turned out to be a super way to start learning how fiddle tunes are put together, and start developing an ear. I got two of the most common tune books: Dave Brody's Fiddler's Fake Book, and Susan Songer's The Portland Collection.

At first the chord progressions seem to just fly by without making much sense. Sometimes it's as fast as one chord per beat at 2 beats per second. But some things began to make sense:

- Most fiddle tunes have two sections, with one or more contrasting characteristics. One section might be low in the fiddle range, the other high. One section might have very few chord changes, the other many. One might have all major chords, the other mostly minor. Usually, each section begins on the tonic and ends on the tonic (Even that is not always true, but it starts to become obvious when it isn't).

- Ancient modal and gapped tunes can often be accompanied with only two chords so they're the easiest for a beginner to follow: i (or I) and VII chords. E-dorian and A-dorian tunes are fairly common; consisting mainly or entirely of just E-minor/D-major or A-minor/G-major, respectively. A-mixolydian tunes can typically be accompanied with just A-major/G-major.

- Modern tunes (ie, within the last 300 years or so), tend to have at least 3 chords, usually I (or i), IV, and V. For me, hearing the V to I was easiest to hear first. It especially comes just before the end of a section. Then comes I to V. Picking out the changes to/from IV are harder. vi chords even harder.

- One thing you discover quickly is not everybody harmonizes the same tune the same way. There's a lot of variation. The most commmon variation seems to me to be the I vs VI chord; for example, G vs Em in the key of G major. Also, the ii vs the IV; for example, Am vs C in the key of G major. In many places you could play either one. Often, both of them together can be compatible enough that most people don't notice in a jam situation. But another that's more problematic is the IV vs VI; for example, C vs Em in the key of G major. Here the difference is much more noticeable and the two at the same time are not at all compatible.

- Fiddle tunes don't usually have chromaticism so when it happens it stands out. One of the examples is the VII chord built on the minor seventh degree. For example, a G major chord in something that's decidedly A-major. Does that ring a bell? Ah, it's a throwback to old fashioned A-mixolydian. Purity of musical style is not a big concern for tune writers or accompanists.

- It's still way too hard for me to hear and identify every individual chord change. They go by way too fast, for one thing. But after awhile one thinks of a section as a sentence. Some tunes have the same or very similar standard sentences.

Like: I - - - - - - V - I - - - - - - V - I -

or: I - - - IV - V - I - - IV - V - I -

or: I - IV- I - V - I - IV - V - I -

or: vi - - - - - -I -V - vi - - - - V - I -

Even if it's not one pattern or another, picking a first draft guess can lead to finding the real pattern after a few trials and watching the senior guitarist's left hand.

- I was really thrown for a loop over places where the chord changes every beat. How can anybody hear and follow that? Well, it turns out in practice that happens for one reason: The melody is basically a scale fragment; up or down. So what's a thumpy ol' washtub player to do? The easiest thing to do is to also play a scale fragment, in unison or in parallel. Take, for instance, a melody is |G-BG|F#-AF#|EDC#E|D. When I know the tune well I might play the chordal roots: G-D-A-D, but it's easier and works well for folkie purposes to just play G-F#-E-D.

Ok, when am I getting to cello? Patience! It's coming up next time.

The memory of the washtub bass thumping in the mist persisted. The music of that weekend was dominated by high range instruments. String bass and washtub bass, along with just some guitarists who emphasize bass notes, were the principal exceptions.

I did a little on-line reseach into washtub bass and found that, while there are no instruction guides at all on how to play one, there are many variations and plans on how to make one. One design in particular appealed to me, dubbed Tub-o-Tone by it's inventer, Lauren Miller. It has a fixed neck, a single tunable string, and a simple, to-the-point, no-frills, sound efficient design that appealed to me.

In my research I learned that washtub basses and harps share something unique in the string instrument world. Other instruments, i.e. those with bridges perpendicular to the string, transmit vibrations to the sound chamber at the same pitch as the string itself vibrates. One cycle to one cycle.

Harps and washtub basses, on the other hand, don't have bridges. The string attaches directly out of the sound box. In those cases the top of the sound box is pulled up and let down twice for every one cycle of the string. The pitch one hears from the sound chamber is twice the actual pitch of the string. Oooo, Cool! So that explains how those guys can play notes in the string bass range with ordinary clotheslines at low tension! It also explains how those long thick nylon harp strings sound higher than it appears they should.

By the end of the summer of 2002 I was in the Home Depot selecting materials and building my very own Tub-o-Tone. By fall I was attending local jams. Suffice it to say my unique home-made instrument got a lot attention and compliments; my playing, well, not nearly so much.

But it turned out to be a super way to start learning how fiddle tunes are put together, and start developing an ear. I got two of the most common tune books: Dave Brody's Fiddler's Fake Book, and Susan Songer's The Portland Collection.

At first the chord progressions seem to just fly by without making much sense. Sometimes it's as fast as one chord per beat at 2 beats per second. But some things began to make sense:

- Most fiddle tunes have two sections, with one or more contrasting characteristics. One section might be low in the fiddle range, the other high. One section might have very few chord changes, the other many. One might have all major chords, the other mostly minor. Usually, each section begins on the tonic and ends on the tonic (Even that is not always true, but it starts to become obvious when it isn't).

- Ancient modal and gapped tunes can often be accompanied with only two chords so they're the easiest for a beginner to follow: i (or I) and VII chords. E-dorian and A-dorian tunes are fairly common; consisting mainly or entirely of just E-minor/D-major or A-minor/G-major, respectively. A-mixolydian tunes can typically be accompanied with just A-major/G-major.

- Modern tunes (ie, within the last 300 years or so), tend to have at least 3 chords, usually I (or i), IV, and V. For me, hearing the V to I was easiest to hear first. It especially comes just before the end of a section. Then comes I to V. Picking out the changes to/from IV are harder. vi chords even harder.

- One thing you discover quickly is not everybody harmonizes the same tune the same way. There's a lot of variation. The most commmon variation seems to me to be the I vs VI chord; for example, G vs Em in the key of G major. Also, the ii vs the IV; for example, Am vs C in the key of G major. In many places you could play either one. Often, both of them together can be compatible enough that most people don't notice in a jam situation. But another that's more problematic is the IV vs VI; for example, C vs Em in the key of G major. Here the difference is much more noticeable and the two at the same time are not at all compatible.

- Fiddle tunes don't usually have chromaticism so when it happens it stands out. One of the examples is the VII chord built on the minor seventh degree. For example, a G major chord in something that's decidedly A-major. Does that ring a bell? Ah, it's a throwback to old fashioned A-mixolydian. Purity of musical style is not a big concern for tune writers or accompanists.

- It's still way too hard for me to hear and identify every individual chord change. They go by way too fast, for one thing. But after awhile one thinks of a section as a sentence. Some tunes have the same or very similar standard sentences.

Like: I - - - - - - V - I - - - - - - V - I -

or: I - - - IV - V - I - - IV - V - I -

or: I - IV- I - V - I - IV - V - I -

or: vi - - - - - -I -V - vi - - - - V - I -

Even if it's not one pattern or another, picking a first draft guess can lead to finding the real pattern after a few trials and watching the senior guitarist's left hand.

- I was really thrown for a loop over places where the chord changes every beat. How can anybody hear and follow that? Well, it turns out in practice that happens for one reason: The melody is basically a scale fragment; up or down. So what's a thumpy ol' washtub player to do? The easiest thing to do is to also play a scale fragment, in unison or in parallel. Take, for instance, a melody is |G-BG|F#-AF#|EDC#E|D. When I know the tune well I might play the chordal roots: G-D-A-D, but it's easier and works well for folkie purposes to just play G-F#-E-D.

Ok, when am I getting to cello? Patience! It's coming up next time.

Bodhrán side-track

PFS asked about that drum in Morrison's Jig/God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen. That's a bodhrán, pronounced bow-rawn, that looks like:

and played with a short stick that looks like:

A player might play something like this, with a mixture of open and muffled tones:

Too much bodhrán gets old mighty fast, hence a plenitude of bodhrán jokes. Here's a clip from a recent movie with a bit of bodhrán in the mix: Road to Perdition clip

and played with a short stick that looks like:

A player might play something like this, with a mixture of open and muffled tones:

Too much bodhrán gets old mighty fast, hence a plenitude of bodhrán jokes. Here's a clip from a recent movie with a bit of bodhrán in the mix: Road to Perdition clip

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Teachers

Below is a repeat of something I posted on ICS's CBN yesterday. Perhaps someone may respond here, or pick it up on his/her own blog, differently than they would post over there with the thought-police.

In echo of the recent thread on what makes a good cello, what makes a good teacher? And, are good teachers rarer than good cellists?

Recent posts have prodded me, but I've been planning to start a thread on this subject for months. I'm sure the answer varies depending on the student, but I also imagine there are some constants.

My first teacher, whom I had for a year and a half, was an undergraduate student with limited cello performance and teaching experience. My second teacher has a Master's degree in Cello Performance and rather extensive performance experience in the US, Europe, and recently, Australia. Yet, I am struck more by their similarities in teaching much more than their differences. Yes, there have been differences in emphasis, and some things one mentions but not the other. But nothing from the first teacher has been undone or contradicted by the second. Both teachers have presented things within a framework that makes logical sense to me, so even if I can't do something well right away, I feel I understand where I'm heading.

Also, both teachers have tolerated, even welcomed, my sidetracks and off-the-wall questions. Both teachers patiently understood that I'm not just going to take their word for it, I'm going to have to experience it and sort it out for myself. It has to make sense by my understanding of how music, the physical world, levers, and the human body work, not just platitudes and simplistic catch-phrases that sometimes ignore physical reality.

Both teachers themselves, are active in both classical and non-classical cello, although their non-classical pursuits are immensely different.

Also, both teachers made me much more aware of how I actually sound than I would otherwise hear. It's so difficult to hear ourselves and play at the same time. Learning and playing takes up so much attention, there's precious little attention power left for listening.

When I read the ICS newsletter interviews, even as a very beginner, one thing struck me about what these artists appreciated about their teachers. They most appreciated the teachers that gave them strategies for solving new future problems rather than providing specific pat answers to specific current problems. That says something about the teacher, but even more about the student!

To my perspective, there's quite a few accomplished cellists in the world. I'm surprised at how many skilled or formerly skilled cellists are around, although few earn a full living performing. Few earn a living performing music in any area.

But really good teachers? I suspect they are far rarer. It seems to me few understand how it is they do what they do, and can transfer what it into another individual. Even more rare, I would think, is the truly effective match between student and teacher. Clearly, no teacher is right for everyone at every point in a musician's trainig.

I have told my teacher that someday, years (many years!) from now, I'd like to teach. She said (maybe lied) that I'd make a great teacher (Bob & Rich's worst nightmare, I know. They'll have to add a caveat to the ol' "Get a teacher" refrain). See! All the more reason for y'all to not just get any teacher!

In echo of the recent thread on what makes a good cello, what makes a good teacher? And, are good teachers rarer than good cellists?

Recent posts have prodded me, but I've been planning to start a thread on this subject for months. I'm sure the answer varies depending on the student, but I also imagine there are some constants.

My first teacher, whom I had for a year and a half, was an undergraduate student with limited cello performance and teaching experience. My second teacher has a Master's degree in Cello Performance and rather extensive performance experience in the US, Europe, and recently, Australia. Yet, I am struck more by their similarities in teaching much more than their differences. Yes, there have been differences in emphasis, and some things one mentions but not the other. But nothing from the first teacher has been undone or contradicted by the second. Both teachers have presented things within a framework that makes logical sense to me, so even if I can't do something well right away, I feel I understand where I'm heading.

Also, both teachers have tolerated, even welcomed, my sidetracks and off-the-wall questions. Both teachers patiently understood that I'm not just going to take their word for it, I'm going to have to experience it and sort it out for myself. It has to make sense by my understanding of how music, the physical world, levers, and the human body work, not just platitudes and simplistic catch-phrases that sometimes ignore physical reality.

Both teachers themselves, are active in both classical and non-classical cello, although their non-classical pursuits are immensely different.

Also, both teachers made me much more aware of how I actually sound than I would otherwise hear. It's so difficult to hear ourselves and play at the same time. Learning and playing takes up so much attention, there's precious little attention power left for listening.

When I read the ICS newsletter interviews, even as a very beginner, one thing struck me about what these artists appreciated about their teachers. They most appreciated the teachers that gave them strategies for solving new future problems rather than providing specific pat answers to specific current problems. That says something about the teacher, but even more about the student!

To my perspective, there's quite a few accomplished cellists in the world. I'm surprised at how many skilled or formerly skilled cellists are around, although few earn a full living performing. Few earn a living performing music in any area.

But really good teachers? I suspect they are far rarer. It seems to me few understand how it is they do what they do, and can transfer what it into another individual. Even more rare, I would think, is the truly effective match between student and teacher. Clearly, no teacher is right for everyone at every point in a musician's trainig.

I have told my teacher that someday, years (many years!) from now, I'd like to teach. She said (maybe lied) that I'd make a great teacher (Bob & Rich's worst nightmare, I know. They'll have to add a caveat to the ol' "Get a teacher" refrain). See! All the more reason for y'all to not just get any teacher!

Sunday, December 03, 2006

Morrison's Gentlemanly Medley

"Well, how did the performance at the mall go?", I hear you cry. Ok, you didn't cry; I just have a wildly hyperactive imagination.

Our first Christmas gig went reasonably well considering it was our first performance for most of the tunes and the limited time we had to prepare with us altogether. Children danced joyfully. Shoppers stopped and swayed. I even saw a few sing along. Middle-aged men sat and passed the time with us while, presumably, their wives were helping mall retailers boost year-end revenue figures. And I understand the agent that hired us was quite pleased with us. With that going for us, what's a few rhythm and intonation problems in a noisy shopping mall between friends?

We played three 45-minute sets so we had a good bit of Christmas music prepared besides God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen, but that's the story I started, so I shall finish it.

As I mentioned, we put GRYMG together with Morrison's Jig (MJ) to Christmas-fy it. For this combination we played MJ twice, GRYMG twice, and MJ twice. MJ, as three of us are now used to playing it, has a cello intro and prominent cello part. I don't remember how I started playing it, maybe by accident, maybe influenced by suggestions of the leader. It's an accompaniment that has evolved some as I've been playing it, mostly getting simpler. The A strain consists entirely of parallel fifiths. I think it makes a strong, gutsy, modern rock-ish sound, but in any basic classical music theory class it would earn me a big ol' F.

MJ traditionally moves along at a fast clip. Reminds me of a joke a hammer dulcimer player once told me:

How can you tell when a hammer dulcimer player is at your front door?

The knocking keeps getting faster and faster and faster...

I set up my minidisc recorder just prior to the 3rd hour. I should record myself and ourselves more often. I can tell we were tired from the hours of hammering and sawing. I hear some of my habitual mistakes cropping up along with some new original ones. I have ideas on things to change. Such is life, live performance, and music of the people!. HIPP it often ain't.

Here's MJ and GRYMG.

Post Script: The band leader really likes the A part I play to Morrison's (double stops) and is less satisified with the B part. She wonders what it would sound like if I stayed low to provide more contrast with the dulicimers, and what do you all think? Seems to me even the highest note (D above middle C) is still pretty low, and continued low grumblies throughout would be too much.

But that's part of why I like this folkie sort of music making over, let's say, a Mozart quartet (if' I were ready for such a thing). You can't fuss with and change and experiment with Mozart. He's the boss and you gotta do exactly what he wrote. Otherwise, it's not Mozart anymore.

Our first Christmas gig went reasonably well considering it was our first performance for most of the tunes and the limited time we had to prepare with us altogether. Children danced joyfully. Shoppers stopped and swayed. I even saw a few sing along. Middle-aged men sat and passed the time with us while, presumably, their wives were helping mall retailers boost year-end revenue figures. And I understand the agent that hired us was quite pleased with us. With that going for us, what's a few rhythm and intonation problems in a noisy shopping mall between friends?

We played three 45-minute sets so we had a good bit of Christmas music prepared besides God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen, but that's the story I started, so I shall finish it.

As I mentioned, we put GRYMG together with Morrison's Jig (MJ) to Christmas-fy it. For this combination we played MJ twice, GRYMG twice, and MJ twice. MJ, as three of us are now used to playing it, has a cello intro and prominent cello part. I don't remember how I started playing it, maybe by accident, maybe influenced by suggestions of the leader. It's an accompaniment that has evolved some as I've been playing it, mostly getting simpler. The A strain consists entirely of parallel fifiths. I think it makes a strong, gutsy, modern rock-ish sound, but in any basic classical music theory class it would earn me a big ol' F.

MJ traditionally moves along at a fast clip. Reminds me of a joke a hammer dulcimer player once told me:

How can you tell when a hammer dulcimer player is at your front door?

The knocking keeps getting faster and faster and faster...

I set up my minidisc recorder just prior to the 3rd hour. I should record myself and ourselves more often. I can tell we were tired from the hours of hammering and sawing. I hear some of my habitual mistakes cropping up along with some new original ones. I have ideas on things to change. Such is life, live performance, and music of the people!. HIPP it often ain't.

Here's MJ and GRYMG.

Post Script: The band leader really likes the A part I play to Morrison's (double stops) and is less satisified with the B part. She wonders what it would sound like if I stayed low to provide more contrast with the dulicimers, and what do you all think? Seems to me even the highest note (D above middle C) is still pretty low, and continued low grumblies throughout would be too much.

But that's part of why I like this folkie sort of music making over, let's say, a Mozart quartet (if' I were ready for such a thing). You can't fuss with and change and experiment with Mozart. He's the boss and you gotta do exactly what he wrote. Otherwise, it's not Mozart anymore.

Friday, December 01, 2006

Less is more, more or less

Well, at practice with the two hammer dulcimers I found I had to toss out and re-think my accompaniment to God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen (GRYMG). We are doing other Christmas tunes, along with a few non-Christmas tunes, but I think the story illustrates how things typically develop as I try to come up with my own notes.

Our fearless leader has placed Morrison's jig into a medley that leads into GRYMG, with the guitar player playing bohdran (a type of drum, pronounced bow-ron) instead of guitar. That means my cello will provide the only harmony.

Both tunes are, nominally, in E minor, but that's about where the similarity usually ends. GRYMG, as usually harmonized and performed, is in classical E minor. The melody technically fits the Aeolian mode but traditionally with the 6th and 7th degrees raised or lowered in the harmony lines to enhance harmonic richness and make for interesting alto, tenor, and bass parts .

However, the melody itself has no altered tones. By itself it's just good ol' simple, primitive Aeolian. And that's what you hear with just two dulcimers playing melody with no harmony to "classicalize" it.

Morrison's jig is even more primitive. Our version consists almost entirely of a gapped scale. Of the 100 or so notes, the sixth degree appears only once, and then as a very quick passing tone, and it's raised, ie Dorian mode. However, the sixth degree is so brief that the tune's commitent to Dorian is negligible. The tune is mostly just notes of the E minor chord alternating with notes of the D major chord.

Also, the tempo of Morrison's jig is quite fast. The thump-ity thump-ity of the drum moves us right along. That means our GRYMG will move along like that proverbial bat from the underworld.

So, from a melody-only point of view, these tunes are quite compatible. With the bodhran tying them together, it brings out the primitive modal character of the GRYMG melody. My accompaniment, stripped of the guitar chords, and moving a mile a minute, didn't make a lick of sense anymore. It was introducing a mix of D#s, D naturals, C#s, and C naturals into the fray in a harmonic way of thinking that requires the cooperation of other, no longer existing, harmonic notes. Back to the drawing board.

Ok, so now I have another idea. GRYMG is largely a series of fast moving scale fragments. If my notes are the only non-melody tones, why not just moving scale fragments too, but slow, like a countermelody. Forget about following any chord changes or making up nee chord changes; it's going to work. I'll make my own slow moving solo melody and pretend those other instruments are accompanying me :-)

In ABC notation:

K:Em

L:1/4

z[]e4|d4|c4|B3z|e4|d,4|c4|B3z|

a4|g2f2|e4|d4|e4|d4|c2B2|d2df|g2fe|d2ed|e3[]

(Note: For ease of eading I've written this two octaves above what I actually intend. The notation rules for indicating notes below middle C make it harder to read for someone unaccustomed to ABC notation. At this point what anticipate I'll play for this tune will all be within the bass clef staff. The 4s mean the preceeding note is held 4 times as long as the default length, 2s means the preceeding note is held twice as long at the defail length. L: 1/4 indicates the default length is the quarter note. K:Em indicates the key and default key signature is that for E minor. The z represents a rest; a quarter rest because that's the default length. [] is a double bar. I should get adept at reading ABC notation so I might as well just jump right into it and use it.)

Our fearless leader has placed Morrison's jig into a medley that leads into GRYMG, with the guitar player playing bohdran (a type of drum, pronounced bow-ron) instead of guitar. That means my cello will provide the only harmony.

Both tunes are, nominally, in E minor, but that's about where the similarity usually ends. GRYMG, as usually harmonized and performed, is in classical E minor. The melody technically fits the Aeolian mode but traditionally with the 6th and 7th degrees raised or lowered in the harmony lines to enhance harmonic richness and make for interesting alto, tenor, and bass parts .

However, the melody itself has no altered tones. By itself it's just good ol' simple, primitive Aeolian. And that's what you hear with just two dulcimers playing melody with no harmony to "classicalize" it.

Morrison's jig is even more primitive. Our version consists almost entirely of a gapped scale. Of the 100 or so notes, the sixth degree appears only once, and then as a very quick passing tone, and it's raised, ie Dorian mode. However, the sixth degree is so brief that the tune's commitent to Dorian is negligible. The tune is mostly just notes of the E minor chord alternating with notes of the D major chord.

Also, the tempo of Morrison's jig is quite fast. The thump-ity thump-ity of the drum moves us right along. That means our GRYMG will move along like that proverbial bat from the underworld.

So, from a melody-only point of view, these tunes are quite compatible. With the bodhran tying them together, it brings out the primitive modal character of the GRYMG melody. My accompaniment, stripped of the guitar chords, and moving a mile a minute, didn't make a lick of sense anymore. It was introducing a mix of D#s, D naturals, C#s, and C naturals into the fray in a harmonic way of thinking that requires the cooperation of other, no longer existing, harmonic notes. Back to the drawing board.

Ok, so now I have another idea. GRYMG is largely a series of fast moving scale fragments. If my notes are the only non-melody tones, why not just moving scale fragments too, but slow, like a countermelody. Forget about following any chord changes or making up nee chord changes; it's going to work. I'll make my own slow moving solo melody and pretend those other instruments are accompanying me :-)

In ABC notation:

K:Em

L:1/4

z[]e4|d4|c4|B3z|e4|d,4|c4|B3z|

a4|g2f2|e4|d4|e4|d4|c2B2|d2df|g2fe|d2ed|e3[]

(Note: For ease of eading I've written this two octaves above what I actually intend. The notation rules for indicating notes below middle C make it harder to read for someone unaccustomed to ABC notation. At this point what anticipate I'll play for this tune will all be within the bass clef staff. The 4s mean the preceeding note is held 4 times as long as the default length, 2s means the preceeding note is held twice as long at the defail length. L: 1/4 indicates the default length is the quarter note. K:Em indicates the key and default key signature is that for E minor. The z represents a rest; a quarter rest because that's the default length. [] is a double bar. I should get adept at reading ABC notation so I might as well just jump right into it and use it.)

All of this is well and good except for one thing. The performance at the mall is tomorrow so I won't get a chance to try it out with the others. Yikes!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)